The Family Tree to Better Apples

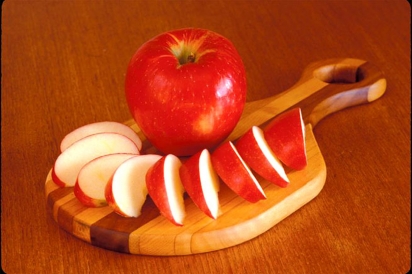

People are falling in love with apples again, and for good reasons. The newest apples on the market, Honeycrisp and SweeTango®, are juicy, sweet tangy, and pack a big crunch — all the top qualities that people want in the perfect apple.

The course to the perfect apple has been a long and patient one. Apple seeds crossed the Atlantic with the first European settlers. By the Civil War, apple trees were plentiful but great-tasting fruit were few.

Most apples ended up in hard cider. At the start of the twentieth century, the apple’s health benefits were promoted and research began to locate and propagate a better tasting apple. By the 1960’s, most grocery stores offered the three basics: McIntosh, Red Delicious and Golden Delicious. More recently shoppers can find a few more varieties, including the newest apple hybrids –Honeycrisp and SweeTango ®.

Door County has had a unique opportunity to be involved with both hybrid apples from the start. In the early 1990’s, the University of Wisconsin Peninsular Research Station (PRS) in Sturgeon Bay was the first place in Wisconsin to grow Honeycrisp. Door County’s Wood Orchard was one of the first orchards to grow Honeycrisp in a big way and, in a unique management of the release of SweeTango®, is the only Wisconsin grower of the newest apple. “Twenty years ago my dad went to the Peninsular Research Station here in Door County and picked and ate the Honeycrisp apple. The next year we began growing it. Now we have close to 30,000 trees in the ground,” said Steve Wood of Wood Orchard and Wood Orchard Market in Egg Harbor. “It is really a popular apple … It has brought many people back to eating apples.”

Released in 1991, the Honeycrisp is prized for its sweetness, firmness, and tartness. It is perfect for eating raw and boasts a long shelf life when stored in cool, dry conditions. Honeycrisp was one of the few hybrid apples that work well with Door County’s short, cold growing season. “We like to say that Door County is the comfort level for Honeycrisp for color and flavor,” Wood said.

Honeycrisp grew at the PRS several years without many accolades.

“The first time I realized they were special was when we were putting apples away in the cooler. I bit into one; it was crispy and juicy like a lot of apples are when harvested. I set it down outside the cooler and a week later noticed it had not changed much. A normal apple would have rotted, so I took a bite … It was still as crisp,” said PRS Superintendent Matt Stasiak. “The crispness and the juiciness has become the gold standard everyone is shooting for now.”

As simple as the birds and the bees

Hybridizing the perfect apple takes time, patience, and sensitive taste buds. Developing Honeycrisp took 30 years. SweeTango® got a little help from DNA testing advances and was released in 21 years. Both apples are products of the 106-year-old University of Minnesota’s (UM) apple-breeding program.

Apple breeding is as simple as the story of the birds and the bees. Pollen is taken from one apple variety and applied to the blossoms of another. Controlled, natural pollination creates hybrid seeds, 3,000 to 5,000 which are then planted in the UM’s greenhouse. The seedlings are screened for traits then transplanted into high density research orchards. The process is repeated every year.

David Bedford, apple breeder for UM and responsible for the Honeycrisp and SweeTango® hybrids, evaluates apples for 20 traits, looking for improved traits worth keeping — which are precious and few.

The two most important are superior texture and flavor. To evaluate texture and flavor, Bedford takes a bite of 500 to 600 apples a day in harvest season. Fortunately he just has to chew, swallow the juice, and spit out the pulp. Even with all that effort, the odds of finding an outstanding specimen are slim.

“Most of the apples I taste and trees I look at get thrown away. About 2,000 to 3,000 get cut down and maybe 10 to 15 get marked for further testing. By the time you go through that process and narrow down the good, the bad, and the ugly, you only get a winner out the other end every so often. It takes 20,000 seeds and young seedlings to find one variety we release to the public,” Bedford said.

An apple by any other name is not as sweet

Bedford’s most recent winner is SweeTango®which debuted in 2009. It is good for eating and cooking. SweeTango’s ® parents are Honeycrisp and Vestar, an earlier apple, and it follows Vestar’s ripening trait, ripening several weeks earlier than Honeycrisp. Although it has not been on the market long, it has many fans. “SweeTango® is the best apple I have ever eaten,” Wood said. “It has a lot of the same qualities of Honeycrisp but with a sweet and tart flavor when the apple is mature.”

Bedford describes SweeTango® as having a complex flavor with “more intensity, more sugar, and more acid.” Basically it is all the things people love about Honeycrisp but packs an even better taste punch and is easier to grow, too.

A twist on the typical release, SweeTango ® is not really SweeTango® until the fruit is picked, sorted, and bagged for sale. The trees and fruit are technically called “Minneiska”. SweeTango® is copyrighted and trademarked so when the patent runs out in 17 years, the UM will still have the control over the name and logo, unlike Honeycrisp. Growers pay a royalty for each tree planted and every pound of SweeTango® that is grown. The managed release is a new approach for apple growing but is not uncommon in other areas of study.

“It is not unusual in universities; lots of things are intellectual property like mining techniques, medical research and other plants that have been developed like cranberries, soybeans and corn. In the apple world, this was quite novel to come out of a public breeding program and deal with that the way they did,” Wood said. “But there are very few public breeding programs left — just Cornell, Minnesota, and Washington State. Everything else is private individuals or companies primarily because it is expensive and the results take so long.”

Only the 45 member growers in the Next Big Thing (NBT) Co-op are allowed to grow SweeTango®. Wood Orchards is the single member of NBT Co-op in Wisconsin; other NBT Co-op members are located in New York, Michigan, Nova Scotia, Quebec, Minnesota and Washington.

This fall the largest crop of SweeTango® will be taken to market in grocery stores around the country for a limited time.

“We like the idea of bringing seasonality back because that is when the fruit is the best … There is excitement in the foods that you have to get while they are here in season or you have to wait a year like Copper River salmon, fiddle head ferns, or ramps. We want to sell SweeTango® during peak eating season,” said Tim Byrne, NBT Co-op President.

Apple growing methods have changed

Along with apple varieties, growing techniques have changed tremendously over the last quarter century from the size of the trees, crop loads and density of plantings. Now apples are grown on dwarf apple tree root stock — trees that are less than ten feet high and four feet wide — and are easier to manage and harvest. Production and quality have increased as the trees put much more energy into growing fruit.

Apple trees are also planted more densely. In the past, 150 apple trees were planted per acre; now 1,000 trees are planted per acre. The trees also bear fruit more quickly — in two or three years instead of six or seven because there is less shade on the fruit. Less shade produces better apple size, higher sugar content, better flavor and a higher quality apple.

Another improvement in growing apples is the way pests are handled. Insecticide and fungicide that was once routinely applied is now only used when economic and environmental thresholds are met.

Honeycrisp’s peculiarities deem it grower unfriendly as it takes a lot more work and attention to grow a high quality crop of Honeycrisp than tried and true varieties like Macintosh. Honeycrisp is a biannual fruit bearer. One year it produces heavily and the next year’s crop is light or not at all. Apple growers learned to tame back the high yield of the trees to help the following year’s production by reducing the blossom by hand and chemical thinning methods.

Bill Roethle, owner of Hillside Orchard in Casco, began planting Honeycrisp as soon as he purchased the orchard 16 years ago. Although he offers pick-yourown for most of the apples at his orchard, Honeycrisp is absent from that list due to the nature of the fruit.

“It doesn’t ripen uniformly on the trees. We go through and hand pick three times each season. The key is timely picking,” Roethle said.

Fortunately for growers, SweeTango® is not as difficult to grow as Honeycrisp. It is not as biannual and seems to be more naturally thinning.

Having two hybrid apples be so well received by growers and consumers is the bee’s knees to Bedford.

“That makes it all worthwhile. You never get that one moment of celebration; it is a gradual process … But we have more of those moments now like when Honeycrisp was named the state apple of Minnesota. It is very gratifying to see them doing well.”